|

||

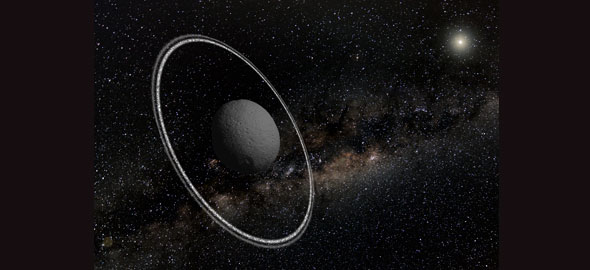

First Ring System Around Asteroid

Science was only aware of those structures on planets like Saturn and Neptune.

Observations at many sites in South America, including ESO’s La Silla Observatory, have made the surprise discovery that the remote asteroid Chariklo is surrounded by two dense and narrow rings. This is the smallest object by far found to have rings and only the fifth body in the Solar System — after the much larger planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — to have this feature. The origin of these rings remains a mystery, but they may be the result of a collision that created a disc of debris. The new results are published online in the journal Nature on 26 March 2014.

The rings of Saturn are one of the most spectacular sights in the sky, and less prominent rings have also been found around the other giant planets. Despite many careful searches, no rings had been found around smaller objects orbiting the Sun in the Solar System. Now observations of the distant minor planet [1] (10199) Chariklo [2] as it passed in front of a star have shown that this object too is surrounded by two fine rings.

"We weren’t looking for a ring and didn’t think small bodies like Chariklo had them at all, so the discovery — and the amazing amount of detail we saw in the system — came as a complete surprise!" says Felipe Braga-Ribas (Observatório Nacional/MCTI, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) who planned the observation campaign and is lead author on the new paper.

Chariklo is the largest member of a class known as the Centaurs [3] and it orbits between Saturn and Uranus in the outer Solar System. Predictions had shown that it would pass in front of the star UCAC4 248-108672 on 3 June 2013, as seen from South America [4]. Astronomers using telescopes at seven different locations, including the 1.54-metre Danish and TRAPPIST telescopes at ESO’s La Silla Observatory in Chile [5], were able to watch the star apparently vanish for a few seconds as its light was blocked by Chariklo — an occultation [6].

But they found much more than they were expecting. A few seconds before, and again a few seconds after the main occultation there were two further very short dips in the star’s apparent brightness [7]. Something around Chariklo was blocking the light! By comparing what was seen from different sites the team could reconstruct not only the shape and size of the object itself but also the shape, width, orientation and other properties of the newly discovered rings.

The team found that the ring system consists of two sharply confined rings only seven and three kilometres wide, separated by a clear gap of nine kilometres — around a small 250-kilometre diameter object orbiting beyond Saturn.

"For me, it was quite amazing to realise that we were able not only to detect a ring system, but also pinpoint that it consists of two clearly distinct rings," adds Uffe Gråe Jørgensen (Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Denmark), one of the team. "I try to imagine how it would be to stand on the surface of this icy object — small enough that a fast sports car could reach escape velocity and drive off into space — and stare up at a 20-kilometre wide ring system 1000 times closer than the Moon." [8]

Although many questions remain unanswered, astronomers think that this sort of ring is likely to be formed from debris left over after a collision. It must be confined into the two narrow rings by the presence of small putative satellites.

"So, as well as the rings, it’s likely that Chariklo has at least one small moon still waiting to be discovered," adds Felipe Braga Ribas.

The rings may prove to be a phenomenon that might in turn later lead to the formation of a small moon. Such a sequence of events, on a much larger scale, may explain the birth of our own Moon in the early days of the Solar System, as well as the origin of many other satellites around planets and asteroids.

The leaders of this project are provisionally calling the rings by the nicknames Oiapoque and Chuí, two rivers near the northern and southern extremes of Brazil [9].

Notes

[1] All objects that orbit the Sun, which are too small (not massive enough) for their own gravity to pull them into a nearly spherical shape are now defined by the IAU as being small solar system bodies. This class currently includes most of the Solar System asteroids, near-Earth objects (NEOs), Mars and Jupiter Trojan asteroids, most Centaurs, most Trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs), and comets. In informal usage the words asteroid and minor planet are often used to mean the same thing.

[2] The IAU Minor Planet Center is the nerve centre for the detection of small bodies in the Solar System. The names assigned are in two parts, a number — originally the order of discovery but now the order in which orbits are well-determined — and a name.

[3] Centaurs are small bodies with unstable orbits in the outer Solar System that cross the orbits of the giant planets. Because their orbits are frequently perturbed they are expected to only remain in such orbits for millions of years. Centaurs are distinct from the much more numerous main belt asteroids between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter and may have come from the Kuiper Belt region. They got their name because — like the mythical centaurs — they share some characteristics of two different things, in this case comets and asteroids. Chariklo itself seems to be more like an asteroid and has not been found to display cometary activity.

[4] The event was predicted following a systematic search conducted with the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at ESO’s La Silla Observatory and recently published.

[5] Besides the Danish 1.54-metre and TRAPPIST telescopes at ESO‘s La Silla Observatory, event observations were also performed by the following observatories: Universidad Católica Observatory (UCO) Santa Martina operated by the Pontifícia Universidad Católica de Chile (PUC); PROMPT telescopes, owned and operated by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Pico dos Dias Observatory from the National Laboratory of Astrophysics (OPD/LNA) - Brazil; Southern Astrophysical Research (SOAR) telescope; Caisey Harlingten‘s 20-inch Planewave telescope, which is part of the Searchlight Observatory Network; R. Sandness‘s telescope at San Pedro de Atacama Celestial Explorations; Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa Observatory; Observatorio Astronomico Los Molinos (OALM) — Uruguay; Observatorio Astronomico, Estacion Astrofisica de Bosque Alegre, Universidad Nacional de Cordoba, Argentina; Polo Astronômico Casimiro Montenegro Filho Observatory and Observatorio El Catalejo, Santa Rosa, La Pampa, Argentina.

[6] This is the only way to pin down the precise size and shape of such a remote body — Chariklo is only about 250 kilometres in diameter and is more than a billion kilometres from Earth. Even in the best telescopic views such a small and distant object just appears as a faint point of light.

[7] The rings of Uranus, and the ring arcs around Neptune, were found in a similar way during occultations in 1977 and 1984, respectively. ESO telescopes were also involved with the Neptune ring discovery.

[8] Strictly speaking the car would have to be rather fast — something like a Bugatti Veyron 16.4 or McLaren F1 — as the escape velocity is around 350 km/hour!

[9] These names are only for informal use, the official names will be allocated later by the IAU, following pre-established rules.

More information

This research was presented in a paper entitled “A ring system detected around the Centaur (10199) Chariklo”, by F. Braga-Ribas et al., to appear online in the journal Nature on 26 March 2014.

The team is composed of F. Braga-Ribas (Observatório Nacional/MCTI, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), B. Sicardy (LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, Paris, France [LESIA]), J. L. Ortiz (Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía, Granada, Spain), C. Snodgrass (Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany), F. Roques (LESIA), R. Vieira- Martins (Observatório Nacional/MCTI, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Observatório do Valongo, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Observatoire de Paris, France), J. I. B. Camargo (Observatório Nacional/MCTI, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), M. Assafin (Observatório do Valongo/UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), R. Duffard (Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía, Granada, Spain), E. Jehin (Institut d’Astrophysique de l’Université de Liege, Liege, Belgium), J. Pollock (Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina, USA), R. Leiva (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile), M. Emilio (Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa, Ponta Grossa, Brazil), D. I. Machado (Polo Astronomico Casimiro Montenegro Filho/FPTI-BR, Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil; Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná (Unioeste), Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil), C. Colazo (Ministerio de Educación de la Provincia de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina; Observatorio Astronómico, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina), E. Lellouch (LESIA), J. Skottfelt (Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; Centre for Star and Planet Formation, Geological Museum, Copenhagen, Denmark), M. Gillon (Institut d’Astrophysique de l’Université de Liege, Liege, Belgium), N. Ligier (LESIA), L. Maquet (LESIA), G. Benedetti-Rossi (Observatório Nacional/MCTI, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), A. Ramos Gomes Jr (Observatório do Valongo, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, P. Kervella (LESIA), H. Monteiro (Instituto de Física e Química, Itajubá, Brazil), R. Sfair (UNESP -– Univ Estadual Paulista, Guaratinguetá, Brazil), M. El Moutamid (LESIA; Observatoire de Paris, Paris, France), G. Tancredi (Observatorio Astronomico Los Molinos, DICYT, MEC, Montevideo, Uruguay; Dpto. Astronomia, Facultad Ciencias, Uruguay), J. Spagnotto (Observatorio El Catalejo, Santa Rosa, La Pampa, Argentina), A. Maury (San Pedro de Atacama Celestial Explorations, San Pedro de Atacama, Chile), N. Morales (Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía, Granada, Spain), R. Gil-Hutton (Complejo Astronomico El Leoncito (CASLEO) and San Juan National University, San Juan, Argentina), S. Roland (Observatorio Astronomico Los Molinos, DICYT, MEC, Montevideo, Uruguay), A. Ceretta (Dpto. Astronomia, Facultad Ciencias, Uruguay; Observatorio del IPA, Ensenanza Secundaria, Uruguay), S.-h. Gu (National Astronomical Observatories/Yunnan Observatory; Key Laboratory for the Structure and Evolution of Celestial Objects, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, China), X.-b. Wang (National Astronomical Observatories/Yunnan Observatory; Key Laboratory for the Structure and Evolution of Celestial Objects, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, China), K. Harpsøe (Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; Centre for Star and Planet Formation, Geological Museum, Copenhagen, Denmark), M. Rabus (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile; Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany), J. Manfroid (Institut d’Astrophysique de l’Université de Liege, Liege, Belgium), C. Opitom (Institut d’Astrophysique de l’Université de Liege, Liege, Belgium), L. Vanzi (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile), L. Mehret (Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa, Ponta Grossa, Brazil), L. Lorenzini (Polo Astronomico Casimiro Montenegro Filho/FPTI-BR, Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil), E. M. Schneiter (Observatorio Astronómico, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina; Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Argentina; Instituto de Astronomía Teórica y Experimental IATE–CONICET, Córdoba, Argentina; Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina), R. Melia (Observatorio Astronómico, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina), J. Lecacheux (LESIA), F. Colas (Observatoire de Paris, Paris, France), F. Vachier (Observatoire de Paris, Paris, France), T. Widemann (LESIA), L. Almenares (Observatorio Astronomico Los Molinos, DICYT, MEC, Montevideo, Uruguay; Dpto. Astronomia, Facultad Ciencias, Uruguay), R. G. Sandness (San Pedro de Atacama Celestial Explorations, San Pedro de Atacama, Chile), F. Char (Universidad de Antofagasta, Antofagasta, Chile), V. Perez (Observatorio Astronomico Los Molinos, DICYT, MEC, Montevideo, Uruguay; Dpto. Astronomia, Facultad Ciencias, Uruguay), P. Lemos (Dpto. Astronomia, Facultad Ciencias, Uruguay), N. Martinez (Observatorio Astronomico Los Molinos, DICYT, MEC, Montevideo, Uruguay; Dpto. Astronomia, Facultad Ciencias, Uruguay), U. G. Jørgensen (Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; Centre for Star and Planet Formation, Geological Museum, Copenhagen, Denmark), M. Dominik (University of St Andrews, St Andrews, United Kingdom) F. Roig (Observatório Nacional/MCTI, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), D. E. Reichart (University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, North Carolina [UNC]), A. P. LaCluyze (UNC), J. B. Haislip (UNC), K. M. Ivarsen (UNC), J. P. Moore (UNC), N. R. Frank (UNC) and D. G. Lambas (Observatorio Astronómico, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina; Instituto de Astronomía Teórica y Experimental IATE–CONICET, Córdoba, Argentina).

ESO is the foremost intergovernmental astronomy organisation in Europe and the world’s most productive ground-based astronomical observatory by far. It is supported by 15 countries: Austria, Belgium, Brazil, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. ESO carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities enabling astronomers to make important scientific discoveries. ESO also plays a leading role in promoting and organising cooperation in astronomical research. ESO operates three unique world-class observing sites in Chile: La Silla, Paranal and Chajnantor. At Paranal, ESO operates the Very Large Telescope, the world’s most advanced visible-light astronomical observatory and two survey telescopes. VISTA works in the infrared and is the world’s largest survey telescope and the VLT Survey Telescope is the largest telescope designed to exclusively survey the skies in visible light. ESO is the European partner of a revolutionary astronomical telescope ALMA, the largest astronomical project in existence. ESO is currently planning the 39-metre European Extremely Large optical/near-infrared Telescope, the E-ELT, which will become “the world’s biggest eye on the sky”.

In order to see the original publication at Nature, please click here

|

|

Share | Tweet |

|

||

|